Leading in times of crisis: How healthy optimism works

Crises are as much a part of business as stormy weather at sea. But what if the storm lasts longer? 3 impulses for strong leadership in a crisis.

Change projects frequently provoke resistance, and the criticism expressed is not always fair and objective. This is how you can react when discussion partners present inappropriate arguments.

In companies, there are many occasions for controversy. Whether it’s about the big strategy or a transformation in a single department: In management circles, during Q&As with employees or at the round-table with the Works Council, managers should deal with criticism constructively and avoid not to be taken down the garden path. Those who are familiar with typical patterns of argumentation can more easily refute criticism. We present seven rhetorical tactics which are often used in discussions – consciously or based on gut feelings. How you should handle them depends on the situation. Sometimes the best way is to ignore them, sometimes you should give an appropriate reply.

1. Emotional appeal

Appealing to feelings is a wise move because emotions strongly determine whether or not people support change. Emotional arguments can be inappropriate though if they are to prevent rational thinking. This is true, for example, when someone refers to tradition: “So far, we have always done well with our products / processes / structures.” Whoever expresses himself in this sense wants to take advantage of human laziness or the fear of novelty. In order to support this argument the person may also refer to anecdotes, such as: “Our competitor X wanted to introduce the same IT system in 2018, but in the meantime he has backed down.”

How can you react?

2. Doomsaying or landslide argument

This tactic also triggers emotional reflexes. It supposes that a projected change will cause an avalanche. Let’s assume that a company wants to introduce a more flexible working model. Among other things, this means more remote working days and an open office space without personal desks. Pessimists argue: “If employees are rarely present the workload will become less visible. They will be given more tasks and have to work unpaid overtime at home. The company will save money but the employees will have to pay the bill.”

How can you react?

3. Straw man tactics

People often talk at cross purposes. However, some misunderstandings are intentional. For example: A company’s top management discusses a women’s quota. An opponent argues that female-dominated management teams would disadvantage male aspirants. This pattern is easy to see through – there was no mention of female dominance. The critic is fighting against a “straw man”, i.e. a position that was not taken at all, but simply offers more scope for attack.

How can you react?

4. Defamation of criticism

As we know, a discussion is not only about the matter in hand but also about the authority of a person. In order to claim a dominant position, some speakers denigrate their critics from the outset, with statements like: “Anyone who has an idea of our industry will agree …” Whoever dares to contradict the following argument would disqualify himself – at least that is suggested here.

How can you react?

5. The either/or trap

To enforce a position, some speakers narrow their argument down to two alternatives. One of them sounds acceptable, the other deterrent. Here’s an extreme example: ” Our chemicals division is not innovative enough. So either we increase the budget or we divest the entire division.” In practice, there are usually significantly more alternatives.

How can you react?

6. The perfection trap

Changes are not only positive. That doesn’t make them wrong. But sometimes critics pretend that any solution must be perfect. For example: A department wants to introduce an administration tool, but resistance is stirring at management level. Among other things, they expect that employees will not maintain their data conscientiously – therefore the tool is basically not useful. This is a classic blockade tactic.

How can you react?

7. Attack on the person

Fortunately, direct insults are rare in professional life. However, ad hominem attacks happen quite often: This means assaulting a person in his or her role, for example as CFO, divisional manager or unionist. Ad hominem arguments are usually made in front of an audience, with the aim of undermining trust, e.g. with accusations like this: “It’s obvious that you are over-critical. You are a works council and hope for your re-election.” Or: “It’s logical that you are in favor of the reorganization as you’re head of Department Y, which is supposed to be extended!”

How can you react?

Finally, three general golden rules for controversial discussions:

Crises are as much a part of business as stormy weather at sea. But what if the storm lasts longer? 3 impulses for strong leadership in a crisis.

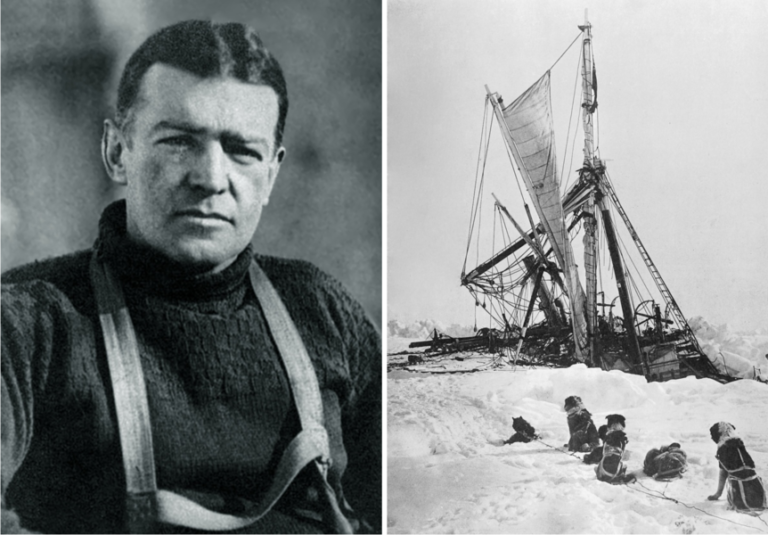

He conveyed confidence in a desperate situation: British polar explorer Ernest Shackleton and his team survived a two-year battle for survival in the Southern Ocean. What can leaders learn from him in times of crisis?

Getting an IT project across hundreds of organizational units to the finish line? Our colleague Mathis takes a sporty approach. In our interview, he tells us what excites him about project management as a consultant and why he goes to the boxing ring to compensate.

2021 Grosse-Hornke Private Consult